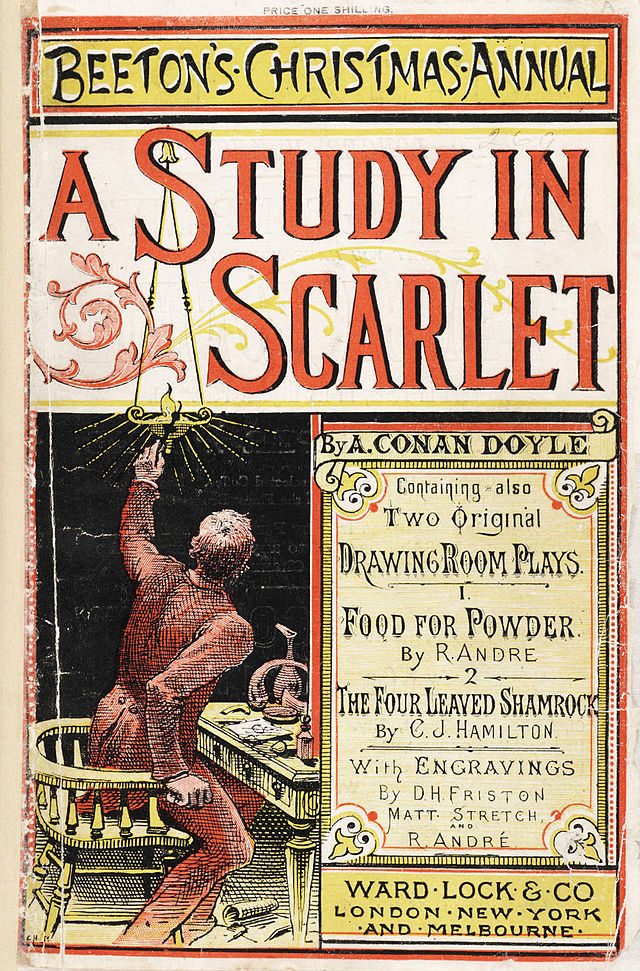

Sherlock Holmes is an iconic character undergoing a bit of a resurgence as of late, with shows like Sherlock and Elementary bringing him into the modern era and a recent pair of blockbuster movies bringing him into the popcorn flick flair. There have been great new editions of the original canon, including impressive annotated editions, and fair-sized run of books introducing new stories with various twists—often a mash-up with a famous historical or literary personage or a bit of horror. There have been audioplays* and stage plays. There have been discussions about whether or not House counts as fully Sherlockian. All in all, not a bad time to be a Baker Street Irregular.

But what happens when you try to release a series of stories inspired by the canon, and you find out that the Arthur Conan Doyle Estate wants you to pay a licensing fee for said collection? The vast majority of the canon—a total of 56 stories and 4 novels—is in public domain, and this includes many of the key stories (e.g., Hound of the Baskervilles, “The Final Problem”, “The Case of the Empty House”, “A Scandal in Bohemia”). However, the very last handful of stories, from The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes are still in copyright, at least in the US (not in the UK, Canada, or Australia). Here’s the question: do the iconic earlier [and public domain] stories which established the character allow you to access it for new material, or do the final [and often considered poorer] stories still hold the character under copyright?

It is not exactly an easy answer. On one hand, a collection of pastiche stories seems like it would be responding to the canon as a whole. Whether or not “The Three Gables” is a good Holmes story, it is a Holmes story written by the original author. On the other hand, copyright when it comes to a character can get complicated. Especially when the person trying to expand the Holmes canon, Leslie Klinger, has an itemized list of key Holmes ideas and from which public domain stories they originate. To wit, as long as they do not use elements unique to the in-copyright stories, then Klinger feels the works are in response only to the canon that does exist in the public domain.

Does Holmes exist as two canons? What’s your gut-take? How about an informed one?

And, presuming you can’t be bothered too much about copyright weirdnesses, here is a post about 10 Interesting Facts about Sherlock Holmes and another with 10 More Interesting Facts about Sherlock Holmes. Those should give you something to munch on.

* Including, interestingly, one where the voice of Holmes is preformed by Nicholas Briggs, the man who does the voice of the Daleks on Doctor Who, which is a cross-canon delight if I have ever heard one.