If you were to stack up the things librarians do, most of them would seem very library-like in what you might call the stereotypical manner: checking out patrons, ordering books, cataloging, helping with research, organizing shelves, maintaining subscriptions, designing library instruction, hosting programs, and so forth. Depending on the size of the library, the type, and so forth, a handful of librarians might do all of those things or each task may have its own team who specializes in it.

One task that often strikes people as weird, those who even know about it, is weeding. This is when a librarian chooses which books to remove from the collection. To some, it seems counter-intuitive: librarians are meant to stockpile knowledge, to archive information, to protect the old documents. And we do those things. Or, more accuratley, those things reflect a portion of what we do. Weeding actually helps to enhance these tasks. That’s why I am going to show you a quick glance into why we do it and how.

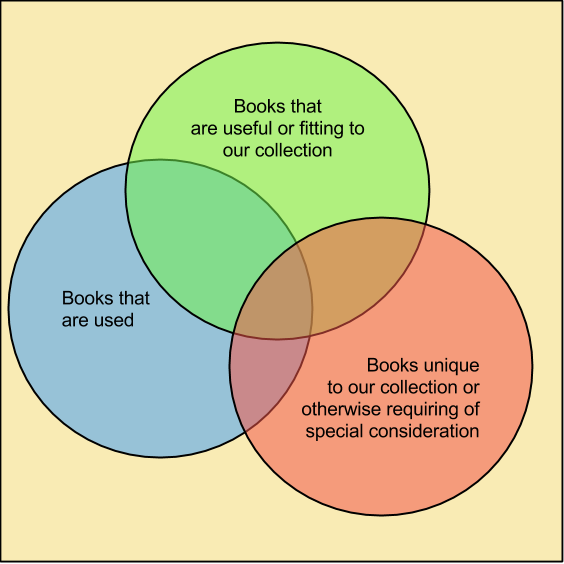

Take a look at this Venn Diagram (more for terminology, and not to scale of any of its parts):

As you look at those broad qualities – Useful Books, Well-Used Books, Books Otherwise Considered – I want you to take note of something the eye might have missed. There are well-used books that may not be useful, there are useful books that may not be well-used, and there are books worthy various considerations that might not be useful or well-used, but, for now, pay attention to the diagram above and notice that there are books that are not useful, not well-used, and not otherwise unique; and sometimes these books take up room on the shelves next to books that are much more fitting as resources.

And that is, very quickly, why we weed. By weeding down the books we have, we make room to order new books, we guarantee the quality of our materials, we help to provide more precise searches – you do not get 100 results where 40 of them are out of date – and it also helps with focusing the mission of the library and to address the many ways the many fields of research on our campus are constantly changing and growing and adapting to more factors than could be easily listed in a blog post of this size. It also helps to find the damaged books [covers torn or pages missing] or otherwise soiled books [it happens]. This helps to cut down on the time we might waste moving these books around, or cleaning/repairing them, or how much time is taken to organize them or to make room around them.

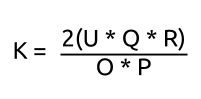

It, of course, is not quite that simple. Rarely is a book completely unique to our collection, completely unused, completely without merit, and so forth [though you might be surprised at how poorly some books weather a decade or two of changes in a field]. So, with the caveat that every librarian has his or her own way of handling the issue [and every type of library has its own general methodologies], something that I use kind of looks like this [with apologies to the Drake Equation]

Where K = a book’s keepability, U = how often the book is used, Q = the quality/importance of the book, R= rarity/special considerations, O = other books on the same topic [especially those of higher quality like later editions], and P = physical defects of the book.

The more used, the higher quality, and the more unique the book, the more likely I will keep it while the more “better” books there are out there and the more physical defects, the less likely I am to keep it. However, due to issues like budgets and with actual use by people trained in the field [professors and students actually using the book] being a better indicator than a review or two posted online, I tend to weigh the top half more than the bottom. I say “twice as weighted” in the equation, but really it is not so easy to sum up. It is always a process of consideration, and multiple factors play into it.

Before I finish, let’s take a quick look at two things that weeding is not.

First off, weeding is not censorship. It could definitely be used for such, but around here the process is used to clean out old books with out of date information that is not being used by our patrons [or is being used by our patrons when we could be identifying and providing more up-to-date information]. As an academic library, we are primarily concerned with staying in line with the needs of the campus, and some of our collection does not fit that. It might have ten or twenty years ago, but two decades is five or so wholly new classes of students, and we have to respect that. We have no interest in keeping certain viewpoints from students’ or professor’s or researcher’s eyes, we are more concerned with the statistics being forty years out of date than espousing a particular worldview. The second part of ALA’s Code of Ethics reads

We uphold the principles of intellectual freedom and resist all efforts to censor library resources,

and we respect and uphold that.

Secondly, weeding is never a faultless panacea. With collections of any size, you have to rely on certain bits of data to generate a list for focus, from which a librarian goes through a number of books [generally related to the librarian’s field of focus] and uses various judgments and considerations, but in every case books tend to be seen in a collective. One stack of books on a topic might have a higher density than books in another stack, and having a dozen choices to weed versus two or three can sometimes lead to books that would not have survived one stack being kept in another. And sometimes there are overlooked elements that might have kept a book if the librarian had time to go page by page or do a complete review of all the literature about the book. That sort of thing. There is also the very real possibility that books may be being used by a number of people, but then placed on the shelf with no record of the use. Believe it or not, this is one of the reasons why we request people not reshelve their own books, it allows us to at least glance what they are taking down from the shelves [the obvious other reason being that if people shelve them wrong, it becomes a disaster fairly quickly]. In the end, the weeding process is only as good as time and data allows, but here at the Salmon Library, we try to use as much of both as possible.

For those curious about the topic and would like to read more, here are some links:

- Weeding Library Collections: A Selected Annotated Bibliography for Library Collection Evaluation – http://www.ala.org/tools/libfactsheets/alalibraryfactsheet15

- CREW: A Weeding Manual for Modern Libraries – https://www.tsl.texas.gov/ld/pubs/crew/index.html

- Awful Library Books: Why We Weed – http://awfullibrarybooks.net/why-weed/

Awful Library Books, whose post, there, has the same rough title as mine [by coincidence of alliteration, I presume], is a great resource to see sort of the semi-humorous side of the weeding process. They show a number of books that have survived being weeded for years, and then discuss why those books should have been long gone. Their discussion brings up many good points. In general, think of their tagline: “hoarding isn’t collection development”. It’s good advice.

Any topics about libraries or this library in particular you would like to see? I’ll do best to show some more information from behind the scenes and why we do some of thing we do.