When I was a wee lad in grad school (note: this was about four years ago), an argument arose with some classmates because I was reading this or that book on an Amazon Kindle (the second generation, which helps to show how many years ago four might be) and they felt that I was missing the bookness of reading. Phrases like “I only read real books” were brought up, phrases that were a bit ironic in that, to-a-person, all of the ebook detractors were huge fans of audiobooks. [We’ll leave aside that many of those classmates are now, themselves, proud owners of various e-reading devices.]

These arguments helped to highlight a somewhat theoretical question that sometimes showed up in our grad school texts: “What is a book?”The question usually meant itself more in the cataloging sense, the sense of collecting information in a way that we could detail information about the information. We have a catalog, and a shelf, and what goes on the latter and how does it fit in the former?

But in that bit of practical, extracurricular argumentation, we saw another meaning to the question: why are plastic disks [and/or digital downloads] of people reading the book more of a book than a digital representation of the text and illustrations? Is bookness only of personal preference, or can the concept “bookness” be easily delineated based on some rules?

The reason the question is still important, to libraries and librarians and to lovers of information in all forms and shapes, is because society sometimes likes to pretend that such rules are readily apparently. If you do a Google search for “bookless library” you’ll be many results about BiblioTech, Bexar County[, Texas]’s all digital library. It is a interesting concept to watch. It is not so alien to imagine a library doing well going digital-only. We have a lot of users that primarily use our extensive collection of digital books, articles, conferences, and so forth. I can fully appreciate that some patrons will prefer digital, not merely settle for it. Depending on the day, I am often one of those patrons, myself.

However, the news coverage is not that the library is digital, but that it is bookless, an altogether other term. In NPR’s coverage of the “Bookless Public Library” [as the headline reads], the opening paragraph includes the line: “The facility offers about 10,000 free e-books…”

In fact, as it goes down, it starts to sound a lot like any other public library. It has computer labs, and reading space, and offers stuff like children’s reading programs. It is only different in a particular way, and the way that this particular way is discussed is, you might say, in a particular way. There are no doubt some of you who feel the “bookless” appellative is richly deserved, but I feel we must return back to that grad school discussion of all those four years ago: why is, to some at least, an Amazon Kindle displaying a azw3 file not a book while an iPod playing an Audible aax file is? Or why are both of those not books when the exact same information displayed in another format – bound softcover or CD, for instance – are? Do these distinctions serve a purpose? To the library? To the library patron? To the casual, everyday person?

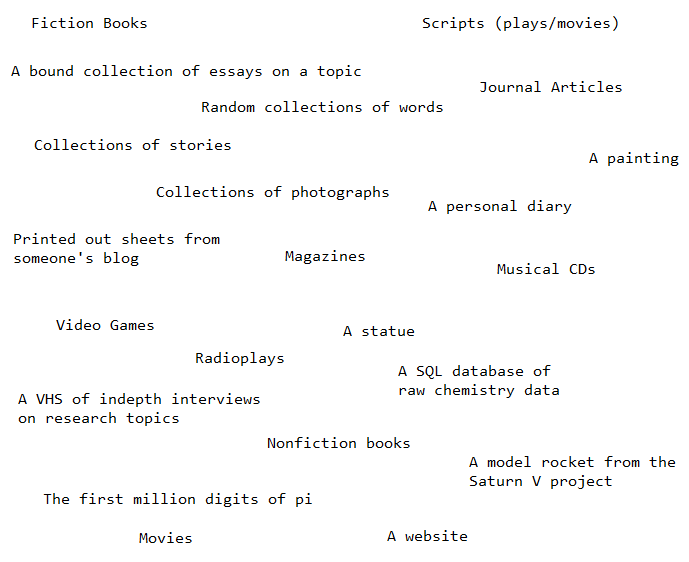

If you will, let us play a a quick word game. Read through this list of things and see which ones feel like “books” to you and which ones feel like “not-books”. It’s a bit a scattered and random [on purpose], but just make through it as you see fit.

Some of these feel obvious. Obviously are books or are obviously not books. But what I want you to consider is that the line will never be a clear one. For instance, why would Wikipedia be not a book while the Encyclopedia Britannica is [note: now that all encyclopedias are going more and more online, assume I’m discussing when they were big and printed bound volumes]? Why would The Diary of Anne Frank be a book, in printed form, while a teen’s online blog about suffering from depression not be? If you printed the latter out, would it transform into a book? Why would a collection of tables to solve TAN and COS and SIN be a book, but the TAN/COS/SIN functions on a calculator aren’t? Does the limits of the former grant it a particular power over the latter?

Are videogames books? How about books that include interactive content? How about interactive content that is fun? How about a game that shows you lots of text about the storyline but requires mild amounts of interacting to progressive? What about one for the old games like Zork? Or the Choose Your Own Adventure books [are they really books]? Or Fighting Fantasy, a similar sort of thing which required you to roll dice and map out your progress? Or how about the new digital remakes of Fighting Fantasy, that roll the dice the dice and automap but still, generally, require you to read all the original text?

Are radioplays, or audioplays [sometimes called full-text audio, like the sort that Big Finish make], books? Are audiobooks where different people read off the lines as the characters books? Are musical albums with definite narrative bent [like some prog rock and folk] books? Are books, like those on some e-reader devices, still books if you click the “text to speech” option? What if you use a device to read the words on the page of a physical, printed out “dead tree” book? Is it still a book if you do not engage it fully in the physical realm?

The point of none of those exercises was to force you to say “EVERYTHING’S A BOOK!!!”, but merely to say that there do seem to be some things that are books and some things that are not books, but the dividing line is unclear and murky at the best of times. And when people are making decisions about libraries with the assumption that libraries are places of books [and book-like things such as journals and maybe maps], and they are applying this definition to the budgets and the running and the governing and the biases of libraries, then what does this mean for libraries? How will this change the fabric of the future of information science, when it gets decided that one collection of information is a book, and fits in a library, and another is not and so should not be in a library?

The twenty-first century information landscape will, at least, be interesting.